An early career researcher’s view on modern and open scholarship

This post constitutes my talk at the OPEN SCIENCE IN PRACTICE 2017 summer school in Lausanne, on the 25 September 2017. The slides used during the presentation are available here.

Here’s a video of a shorter version of this talk, presented in the evening at the EPFL library.

Abstract: If research is the by-product of researchers getting promoted (a quote by David Barron, Professor of Computer Science, Prof. Leslie Carr, personal communication), then shouldn’t we, early career researchers (ECRs), focus on promotion and being docile academic citizens rather than aiming for the more noble cause of pursuing research to understand the world that surrounds us, and disseminate our findings using modern channels? Indeed, I have already argued that a critical point that is failing us, is the academic promotion of open research and open researcher, as a way to promote a more rigorous and sound research process and tackle the reproducibility crisis. In this talk, I will present the case for open scholarship from an early career researcher’s perspective, pointing out that being an open researcher is not only the right thing to do, but is also the best thing to do.

Introduction

I am going to refer to the protagonists of this talk as we, we all. While I will focus specifically on early career researchers 1 (ECRs), I really want to be inclusive, and use ‘we’. The reason is that open research is not only a concern for ECRs - that’s only the main theme of my talk - is concerns us all. In particular, we, ECRs, need more support from senior/established academics, librarians, funders, … Together, each of us in own quality, we need to drive change for a better, more open research environment.

It is also important to highlight that open is not a replacement of good research. I have heard too often that open access is synonym of lesser publication. This is clearly nonsense, and the result of ignorance or the sole desire to harm those that publish on open access venues. We need to work hard to do the best research, and share it openly. As I will argue later, I would even claim that open is a gateway to better research. So let’s not give anyone an opportunity to be confused.

I also tend to refer to open research rather than open science as to not explicitly exclude non-STEM field. And while my views will however resonate with scientists primarily, I believe many of the discussions below should also apply to other communities.

Who?

A few words about myself to offer some context on my view on modern and open scholarship:

I am Laurent Gatto, an early career researcher at the University of Cambridge, UK. I am a Senior Research Associate (non-established research staff) in the department of Biochemistry and a principal investigator in the Cambridge Systems Biology Centre.

My research focuses on the reproducible analysis and interpretation of high-throughput biological data and the development of statistical machine learning methods and research software.

I am a open scholar and make a point of being vocal about it.

What is Open Research/Science

Any research output should be

- Free to read/access: no barriers to access knowledge

- Free to re-use (data, software, text and data mining, …)

But also

- Free to publish (or how the golden OA movement excludes the global south and benefits commercial/hybrid predatory publishers2. See also the pay-to-publish model).

Open research/science should also be

- Inclusive

Open vs. closed?

Let’s first reflect on the nature of science, and whether there really should be anything like explicitly open science.

In 1942, Robert Merton introduced his four Mertonian norms of Science (pdf: The Sociology of Science, a set of institutional imperatives taken to represent the ethos of modern science.

- universalism: scientific validity is independent of the sociopolitical status/personal attributes of its participants

- communalism: all scientists should have common ownership of scientific goods (intellectual property), to promote collective collaboration; secrecy is the opposite of this norm.

- disinterestedness: scientific institutions act for the benefit of a common scientific enterprise, rather than for the personal gain of individuals within them

- organised scepticism: scientific claims should be exposed to critical scrutiny before being accepted: both in methodology and institutional codes of conduct.

Are these imperatives in line with current practice? Status of researchers and their institutions has major influence on their incomes and outputs, and ownership, IP and secrecy are part of research business at the highest level. Personal gain is not unheard of in science (see Danny Kingsley’s recent key note talks at COASP9 for examples of financial rewards for publishing in certain venues). Finally, scepticism is organised and controlled by an elite and validated by commercial publishers. On the other hand, the imperatives are line with principles promoted by open science.

More recently, in 2015, Mick Watson asked the question more directly: When will open science become simply science?.

I claim that open is a gateway to more trustworthy research.

- Open research is research that enables reproducible and repeatable research.

- Open research is transparent and honest research.

- Open research is research that we can build upon.

Open is better, and we should always aim for the better, not the worse.

But then,

Why would anyone not want to do open research?

Note that nobody ever claimed (as far as I know, anyway) to do closed science. And there’s no black-and-white situation between open and non-open/closed. There is always a degree of how far one wants, or can, promote the most open possible research.

Why isn’t it open?

Incentives in for open career progression aren’t there (yet? - see below). On the contrary…

If research is the by-product of researchers getting promoted (a quote by David Barron, Professor of Computer Science, Prof. Leslie Carr, personal communication), then shouldn’t we, early career researchers (ECRs), focus on promotion and being docile academic citizens rather than aiming for the more noble cause of pursuing research to understand the world that surrounds us, and disseminate our findings using modern channels?

In my opinion, barriers are not technological, but rather socio-cultural and political.

- Systemic control and inertia

- Vested interests by people in charge

- Abuse of power dynamics

- Fear of being scooped (update - an editorial in PLoS Biology on The importance of being second and, and how they prefer to focus on complementary research, recognising its important role in reproducibility of science.)

- Fear of not being credited

- Fear of errors and public humiliation, risk for reputation

- Fear of information overload

- …

- Fear of becoming less competitive in a over-competitive market!

While it is important to identify why open can look dangerous to some, I don’t want to spent too much time discussing these points. See Jon Tennant’s recent presentation about Barriers to Open Science for junior researchers on figshare for more details.

The important message at this point is that, many if not all of these fears are only perceived risks. Let’s move on to why ECRs should seriously consider being open researchers.

Go OPEN!

Open science/research is particularly important for ECRs. Open research practices are here, and won’t go away. It is clear that they will increase in the near future. If you, as an ECR, want to be a competitive researcher in the coming years (and you’ll need to be), you’ll need to be well versed in open research practices.

Here, I give some reasons and examples supporting my claims.

Funders’ requirements

- CC-BY open access publication (golden or green) with limited embargo period. In the UK, Wellcome Trust and all RCUK funders.

- Requirement for a data management plan (see here for one of mine)

- Open data mandatory for H2020 grants and many national applications.

- The Wellcome Trust recently expanded it’s data management plan to any research outputs (software, antibodies, cell lines, …) (July 2017).

Acceptance of open practice: pre-prints

- Wellcome Trust (Jan 2017) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) (April 2017) accept pre-prints in grant applications.

- NIH encourages submission of pre-prints and cite them (March 2017).

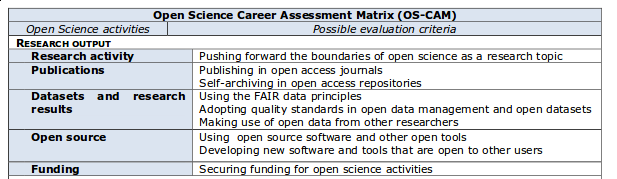

Open science evaluation criteria

The EU’s Evaluation of Research Careers fully acknowledging Open Science Practice defines an Open Science Career Assessment Matrix (OS-CAM):

Reproducibility and open science are starting to matter in tenure and promotion July 14th, 2017, Brian Nosek

In any case, my experience with promotion review requests this summer suggests that change is occurring, particularly in assigning scholarly value to open science contributions and behavior, and it’s great to see.

Open as a career boost

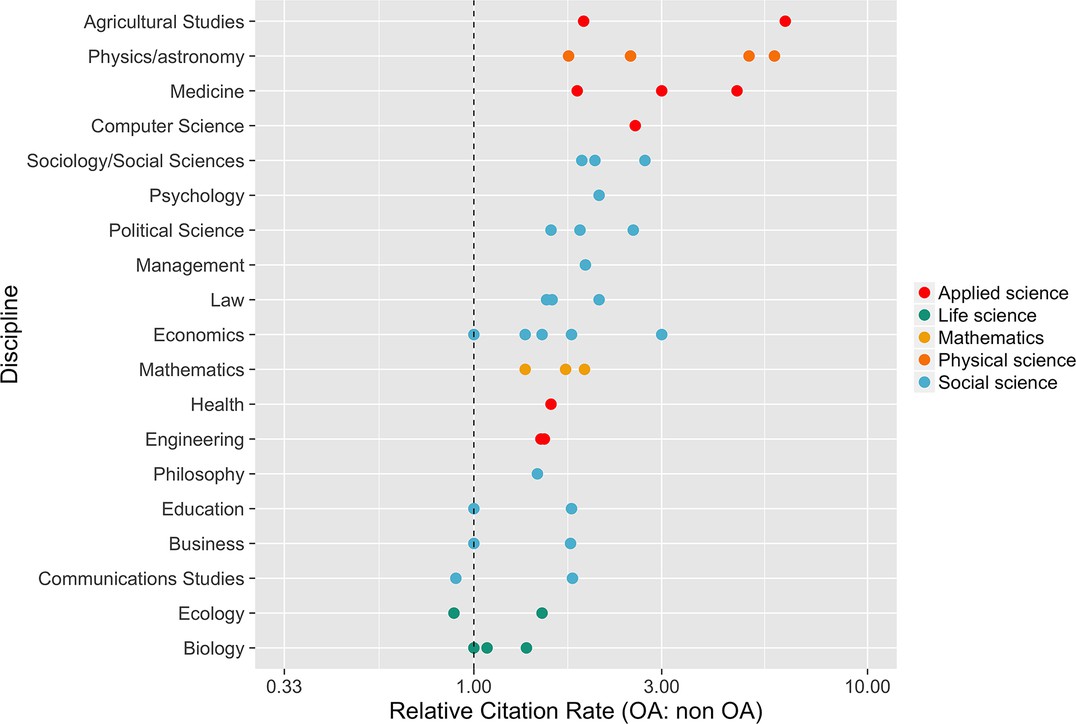

The majority concluded that there is a significant citation advantage for Open Access articles.

From Tennant JP, Waldner F, Jacques DC et al. The academic, economic and societal impacts of Open Access: an evidence-based review. F1000Research 2016, 5:632 (doi:10.12688/f1000research.8460.3)

Open access articles get more citations The relative citation rate (OA: non-OA) in 19 fields of research. This rate is defined as the mean citation rate of OA articles divided by the mean citation rate of non-OA articles.

From Erin C McKiernan et al. Point of View: How open science helps researchers succeed eLife 2016;5:e16800 (doi:10.7554/eLife.16800)

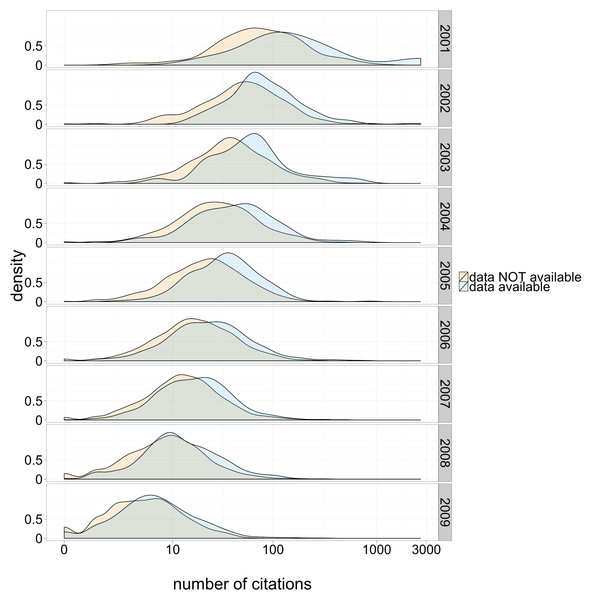

Data availability is associated with citation benefit.

From Piwowar HA, Vision TJ. (2013) Data reuse and the open data citation advantage. PeerJ 1:e175 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.175

See also Why Open Research.

Reproducible research

Who hasn’t hear of the reproducibility crisis? A major underlying factor of the lack of reproducibility is the lack of openness (voluntary or accidental):

- Is the data available and re-usable?

- Is the software available usable?

- Is the method described in enough details?

- …

(More about reproducible research below)

Institutions should worry about research being reproducible and trustworthy, and some argue for it.

We still need more

But, let’s face it, in practice, it is currently still relatively easy to brush over many of these requirements. In addition, the incentives are still inconsequential compared to the (perceived) risks. Maybe we need more threads when not being open.

What can we do?

Build openness at the core your research

Many aspects of open research, and arguable the most important ones, can’t be implemented as an afterthought. You won’t be able to share data that you don’t have anymore, or can’t find. You won’t want to share poor data or ugly code (half-backed, un-annotated, without any documentation), because you’ll look like a fool. You won’t be able to reproduce any results if your don’t make your research repeatable.

In that respect, I want to briefly talk about the SpatialMap project, which aims at producing a visualisation and data sharing platform for spatial proteomics. I decided to promote and drive it as openly as possible in the frame of the Open Research Pilot Project. The ORPP is a joint project by the Office of Scholarly Communication at the University of Cambridge and the Wellcome Trust Open research team. From the official page, the pilot project looks at:

- the support research groups’ need in order to make all aspects of their research open,

- why they want to do this,

- how it benefits them,

- how it improves the research process

- what barriers there might be that prevent the sharing of their research.

Four research groups from Cambridge have been selected to participate. The project proceeds through meetings with all participants (every 6 months), discussions between the research groups and their recognised OSC collaborator, blog posts and occasional emails on a dedicate mailing list. (Here are some early thoughts about the project itself.)

Here are the reasons why the SpatialMap project is an open project:

-

The SpatialMap project in itself is about opening up spatial proteomics data by facilitating data sharing and providing tools to further the comprehension of the data. One aim is to allow users to use the SpatialMap web portal to upload, share, explore and discuss their data privately with collaborators in a first instance (few researchers share their data before publication), then make the data available to reviewer, and finally, once reviewed, make it public at the push of a button. The incentive for early utilisation of the platform is to provide interactive data visualisation and integration with other tools and sharing of the data with close collaborators.

-

The project is developed completely openly in a public GitHub repository3. Absolutely all code and contributions are publicly available. Anyone can collaborate, or even fork the project and build their own.

-

I publicly announced the SpatialMap project in a blog post. The blog post was written as a legitimate grant application (albeit a little bit shorter and sticking to the most important parts).

Note that I do not have any dedicated funding for this project. The progress so far was the result of a masters student visiting my group. Given that the project is not trivial, I am considering applying for dedicated funding to support the project.

Promoting open research through peer review

This section is based on my

The role of peer-reviewers in checking supporting information promoting open science talk.

As an open researcher, I think it is important to apply and promote the importance of data and good data management on a day-to-day basis (see for example Marta Teperek’s 2017 Data Management: Why would I bother? slides), but also to express this ethic in our academic capacity, such as peer review. My responsibility as a reviewer is to

- Accept sound/valid research and provide constructive comments

and hence

- Focus firstly on the validity of the research by inspecting the data, software and method. If the methods and/or data fail, the rest is meaningless.

I don’t see novelty, relevance, news-worthiness as my business as a reviewer. These factors are not the prime qualities of thorough research, but rather characteristics of flashy news.

Here are some aspects that are easy enough to check, and go a long way to verify the availability and validity and of the data

-

Availability: Are the data/software/methods accessible and understandable in a way that would allow an informed researcher in the same or close field to reproduce and/or verify the results underlying the claims? Note that this doesn’t mean that as a reviewer, I will necessarily try to repeat the whole analysis (that would be too time consuming indeed). But, conversely, a submission without data/software will be reviewed (and rejected, or more appropriately send back for completion) in matters of minutes. Are the data available in a public repository that guarantees that it will remain accessible, such as a subject-specific or, if none is available, a generic repository (such as zenodo or figshare, …), an institutional repository (we have Apollo at the University of Cambridge), or, but less desirable, supplementary information or a personal webpage4.

-

Meta-data: It’s of course not enough to provide a wild dump of the data/software/…, but these need to be appropriately documented. Personally, I recommend an

READMEfile in every top project directory to summarise the project, the data, … -

Do numbers match?: The first thing when reproducing someone’s analysis is to match the data files to the experimental design. That is one of the first things I check when reviewing a paper. For example if the experimental design says there are 2 groups, each with 3 replicates, I expect to find 6 (or a multiple thereof) data files or data columns in the data matrix. Along these lines, I also look at the file names (of column names in the data matrix) for a consistent naming convention, that allows to match the files (columns) to the experimental groups and replicates.

-

What data, what format: Is the data readable with standard and open/free software? Are the raw and processed available, and have the authors described how to get from one to the other?

-

License: Is the data shared in a way that allows users to re-use it. Under what conditions? Is the research output shared under a valid license?

Make sure that the data adhere to the FAIR principles:

Findable and Accessible and Interoperable and Reusable

Note that SI are not FAIR, not discoverable, not structured, voluntary, used to bury stuff. A personal web page is likely to disappear in the near future.

As a quick note, my ideal review system would be one where

-

Submit your data to a repository, where it get’s checked (by specialists, data scientists, data curators) for quality, annotation, meta-data.

-

Submit your research with a link to the peer reviewed data. First review the intro and methods, then only the results (to avoid positive results bias).

When talking about open research and peer review, one logical extension is open peer review. While I personally value open peer review and practice it when possible, it can be a difficult issue for ECRs, exposing them unnecessarily when reviewing work from prominent peers. It also can reinforce an already unwelcoming environment for underrepresented minorities. See more about this in the Inclusivity: open science and open science section below.

Be reproducible!

And so, my fellow scientists: ask not what you can do for reproducibility; ask what reproducibility can do for you!

Florian Markowetz.. Five selfish reasons to work reproducibly, Genome Biology 2015 16:274 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0850-7

-

Reproducibility helps to avoid disaster: a project is more than a beautiful result. You need to record in detail how you got there. Starting to work reproducibly early on will save you time later. I had cases where a collaborator told me they preferred the results on the very first plots they received, that I couldn’t recover a couple of month later. But because my work was reproducible and I had tracked it over time (using git and GitHub), I was able, after a little bit of data analysis forensics, to identify why these first, preliminary plots weren’t consistent with later results (and it as a simple, but very relevant bug in the code). Imagine if my collaborators had just used these first plots for publication, or to decide to perform further experiments.

-

Reproducibility makes it easier to write papers: Transparency in your analysis makes writing papers much easier. In dynamic documents (using rmarkdown, juypter notebook and other similar tools), all results are automatically update when the data are changed. You can be confident your numbers, figures and tables are up-to-date.

- Reproducibility helps reviewers see it your way: a reproducible document will tick many of the boxes enumerated above. You will make me very happy reviewer if I can review a paper that is reproducible.

- Reproducibility enables continuity of your work: quoting Florian, “In my own group, I don’t even discuss results with students if they are not documented well. No proof of reproducibility, no result!”.

- Reproducibility helps to build your reputation: publishing reproducible research will build you the reputation of being an honest and careful researcher. In addition, should there ever be a problem with a paper, a reproducible analysis will allow to track the error and show that you reported everything in good faith.

Promoting open research/science

If you want, as an ECR, you can also promote open research/science. Most of the open science supporters are young researchers that want to improve a system they find unhealthy, unfair and does not support good scientific practice.

Promoting open science, especially when done in an constructive way, might also give you an online presence that can be helpful in raising you profile as a researcher.

Open science practice is also a valuable and transferable skill. Good data management and reproducible research might not always be skills that are appreciated in academia, but in many other fields (for example anything related to data science), they are absolutely essential. Science policy is also a very desirable career choice for many STEM graduates, and with the growing importance of open science, these skills would be an important addition to your CV.

You can also support and join open science initiatives. One example I’ll be talking more about is the BulliedIntoBadScience campaign, an initiative by ECRs for ECRs who aim for a fairer, more open and ethical research and publication environment.

What can institutions and senior academics do?

One of the most depressing observations when promoting open research is the lack of support by senior academics, whether they have vested interests, are only mis-informed about open science, or just have no incentive to drive any change. Fortunately, it’s also important to highlight that there are established academics who support open research, but they are a minority.

Here are eight actions that researchers and institutions should follow to improve open research and open ECR:

- Sign the Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), make hiring and promotion criteria explicit and highlight that the content and quality of research outputs are more important than the venue they are published in.

- Positively value the commitment to open research and publishing practices when considering candidates for positions and promotions.

- Endorse immediate open publishing, favouring publications in journals that are 100% open access.

- Endorse posting of pre-prints in recognised pre-print servers to avoid publishing delays that are detrimental to career progress for ECRs.

- Endorse, support and promote the open publication of data and other scientific outputs such as software.

- Educate researchers about publishing practices via public statements, mandatory courses, and inductions that cover open research/data/access, mandates, the hidden costs of traditional publishing and how to protect ECRs from exploitative publishing practices.

- Report to the public how much institutions pay for research to be published, to raise awareness about the significant drain on public funding.

- Make all postdocs and ECRs full voting members of their institutions to increase diversity and stay connected to the changing needs of this underrepresented group.

These points are taken from the BulliedIntoBadScience campaign, an initiative by ECRs for ECRs who aim for a fairer, more open and ethical research and publication environment.

Whether you are an ECR or a senior academic, sign our letter or support us and our campaign!

Funders have a paramount role to play in the promotion of open research. Many, especially the Wellcome Trust in the UK, have established mandates and requirement to promote some aspects of open research, such as open access publication of all the research they fund (see above). There is however much more they can do to actively promote open researcher in general, and open ECR in particular.

Inclusivity: open science and open science

There is

Open Science as in widely disseminated and openly accessible

and

Open Science as in inclusive and welcoming

On being inclusive - Twitter thread by Cameron Neylon:

The primary value proposition of #openscience is that diverse contributions allow better critique, refinement, and application 3/n

— CⓐmeronNeylon (@CameronNeylon) August 10, 2017

It was a damned hard community to break into. Any step I took to be more open, I felt attacked for not doing enough/doing it right.

— Christie Bahlai (@cbahlai) June 4, 2017

As far as I was concerned for a long time (until June 2017 to be accurate - this section is based this Open science and open science post), the former more technical definition was always what I was focusing on, and the second community-level aspect of openness was, somehow, implicit from the former, but that’s not the case.

Even if there are efforts to promote diversity, under-represented minorities (URM) don’t necessarily feel included. When it comes to open science/research URMs can be further discriminated against by greater exposure or, can’t always afford to be vocal.

- Not everybody has the privilege to be open.

- There are different levels in how open one wants, or how open one could afford to be.

- Every voice and support is welcome.

Conclusions

It’s all about research quality and integrity!

Make sure you are ready to be open (for yourself now, your future self, open the your group/institute, or open to the research community or to the public)

- manage and annotate you data

- backup everything up

- open source development

- online presence

- …

and be as open and promote openness as much as you can.

There’s more than one open.

Better research also means more diverse and inclusive research and a inclusive research environment. And, there are many useful ways and levels to be open.

You want to do more. Yes please!

Inertia is very strong in academia. There are many stakeholders involved, and too few that really want to drive change, due to vested interests and the comfort of their position. There are too many battles to fight, so pick yours wisely, otherwise you seriously risk to be exhausted and completely demoralised.

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. - African Proverb

There’s room for innovation and exploration, as well as influencing and advising the current establishment (slower, but as important).

It is not easy to predict where Open Research/Science will get in the future. Open access has had both positive (widening access) and negative effects (when being re-purposed for commercial benefits, see also a recent interview with Leslie Chan, Confessions of an Open Access Advocat). As ECRs, we are the future of research and the future of research dissemination. We mustn’t be afraid of experimenting, debating, and challenging the establishment.

Acknowledgements: I have been influenced by many throughout my ongoing journey towards better (open) research. I would like to thank some of those that have inspired me, either directly or indirectly, along the way. In no particular order, I would like to thank Corina Logan, Stephen Eglen, Marta Teperek, Danny Kingsley, members of the OpenConCam group, Steve Russel, Yvonne Nobis, Bjoern Brembs, Micheal Eisen, Peter Murray-Rust, Rupert Gatti, Tim Gowers, the Bioconductor project, the Software Sustainability Institute, Greg Wilson and the Software/Data Carpentry. And probably many more.

-

ECR can broadly be define as a post-graduate student, a researcher in academia or industry or at a non-governmental organisation who is unemployed or on a temporary contract, or within 10 years of obtaining a permanent post. It doesn’t primarily relate to the age of the person. ↩

-

Predators aren’t the poor quality journals that disseminate spam, these are opportunistic publishers. The real predators are the big traditional and commercial that have taken control of scholarly dissemination and do everything they can to maintain it and maximise their gains. See for example Why Software and data papers are a bad solution to a real problem. ↩

-

Github is an online interface to the

gitversion control software, which allows to track changes in any text file, revert back to any version. On top of a web interface to the version controlling, Github allows to file at track issues, and tremendously facilitate collaborative online development. I use it for pretty all my research and coding projects, papers, collaboration, analysis reports, … ↩ -

There is often no perfect solution, and a combination of the above might be desirable. ↩